The buying power of a dollar has changed drastically over the years. I had no idea just how much it has changed, so I asked Google, who seems to know everything. Google said, “A dollar, in 1929, had the same buying power as $14.42 in 2018.” So, 90 years ago, even a lowly dime was worth $1.44 in today’s purchasing power. I was eight years old in 1929, and I can vouch for the fact that a dime was important money then. It would pay my admission to Frisco’s weekend movie (we called it a picture show), or it would buy a Coke and a double-dip ice cream cone. You can be sure those things were important to an eight-year-old boy.

But, the problem was, how, in 1929, would I get the dimes, or better yet, the dollars to buy things a boy wants? Some of you will remember that 1929 was the year the Great Depression started. The stock market crashed on October 29 of that year, and banks failed all over the land. Frisco had two banks. Banks closed, never to open again, and people lost their life savings. I was one of the victims. I had worked and saved $20 to buy a bicycle, then, in a flash, my “life savings” was gone. So, I had to start over.

Wages, for those who could find work, were very low. Field workers were lucky to get $1 for a long day’s work. The Federal Minimum Wage Law was adopted in 1938, with an initial rate of 25 cents per hour. The rate has increased every 10 years, and, in 2018, was $7.50, but the average amount actually paid these days is more.

That brings me to the rest of the story, which I will call “The Jobs I Have Had.” The story begins when I was five years old. I enjoyed visiting my dad at his barber shop in downtown Frisco. At that time, there was very little traffic in Frisco, so my parents allowed me to ride my tricycle the five blocks from our house to my dad’s shop. One day, when I was visiting there, Mr. Savage, a local banker who was waiting to get a haircut, started talking to me. He learned that I thought I could tap dance, so he offered to pay me a nickel to show him. I gladly obliged by dancing a jig, and he paid me five cents – the first money I ever “earned.”

As time went on, I spent more time at the barber shop, and, from time to time, Dad paid me a dime to sweep the shop. I guess that was the second bit of money I earned. Over time, I became friends with Dusty, the fellow who manned the shop’s shoe-shine stand. I watched him, day after day, as he shined people’s shoes. I was always fascinated as he “popped the rag.” Once, when I was six or seven years old, Dusty was absent, and I was given permission to shine a customer’s shoes. That earned me another dime and set me off on a brief shoe-shining career (any time Dusty was absent), but I never did learn to pop the rag.

As I began to accumulate nickels and dimes, my parents encouraged me to save. They bought me a little savings bank that would take nickels, dimes and quarters and could not be opened until it held a certain amount. I found a cotton field within walking distance of our house and began picking cotton – a very poor way to make a living. It paid 50 cents per hundred pounds of cotton picked, but it took me all day to pick 100 pounds.

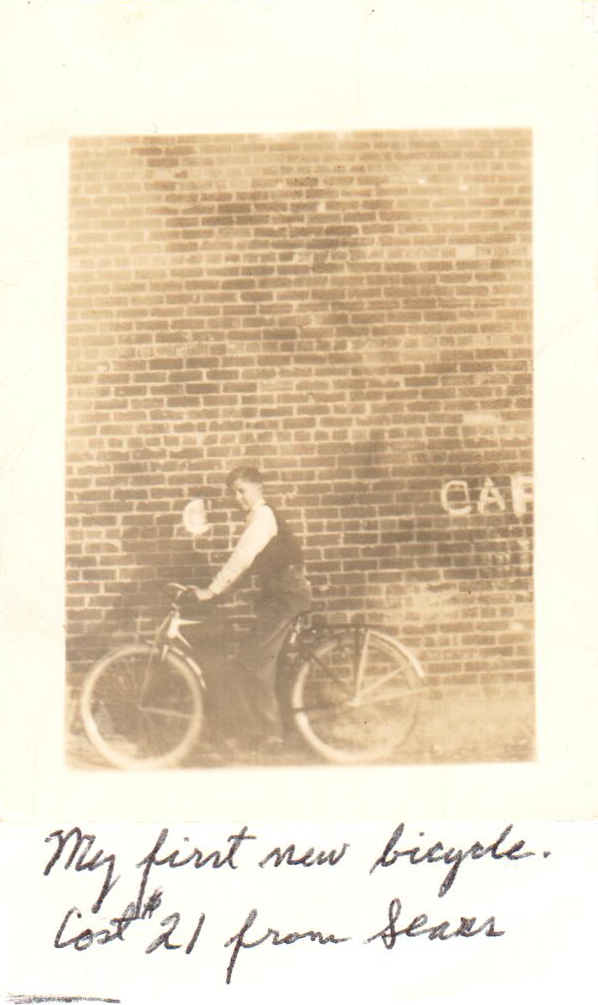

After what seemed like a long time, I saved $9 – enough to buy a used bike. That opened a floodgate of earning opportunities. I got a paper route delivering The Fort Worth Star Telegram, which paid a little more than picking cotton. Later, I got a job collecting and delivering clothes for “Frog” Sapp who ran the local cleaning shop. Before school, I made the rounds to collect clothes from some of the loyal customers, and, after school, I put the clothes on my back, got on my bike and delivered them.

One unusual and short-lived job I had was working for a horticulturist, Mr. Gotcher. He taught me how to bud and graft pecan trees, so I spent a few days climbing trees, applying my newly-learned trade. I still know how to bud and graft, but do not plan to climb any trees.

Perhaps the most interesting and educational job I had as a teenager was working at Curtsinger’s Drug Store. I was a lowly “soda jerk,” but I worked all over the store waiting on the public, young and old. I learned to make malts and to make change using an old-fashioned cash register. It was not much pay but offered a world of experience.

Then, in 1938, I was off to college, where I worked for the National Youth Administration for 50 cents per hour. The three summers between college years were spent working for President Roosevelt’s Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) program, measuring farm land and checking cotton acreage.

After graduating from college in 1942, World War II had started. So, I enlisted in the Army Air Corps Aviation Cadet Program. While waiting to be called to active duty, I worked for Griffin Grain Company in Frisco – a real job, earning $100 per month.

Next, during my active duty, I learned to fly. After graduating from flying school as a commissioned officer, I was sent to Europe, where I earned a hefty $400 per month – the rate for overseas flying pay.

After the war, I joined Humble Oil Company with a starting salary of $250 per month. I worked there for 36 years, retired and came back to Frisco in 1981. That retirement was short-lived. I was elected to the Frisco City Council where I served for 13 years, the last six years as mayor. In those days, Frisco’s mayors and council members were rewarded with a $50-per-month credit to their water bill. Today’s compensation is much more reasonable.

So, you see how much the value and the buying power of our dollar has changed over the years. I believe the work ethic has also changed – for the worse. It seems to me, and I hope I am wrong, that many of today’s children are being given too much of life’s nonessentials, rather than being taught to earn them.

Remember, “freedom is not free,” and neither are life’s necessities, much less our “toys.” That is the end of my sermon!